Issue #1

Stepney And

The Through Line

confessions of a Stepney latecomer

Stepney with daughters Eibur (L) and Charlene (R). Photo courtesy of the Stepney Family

"Are you familiar with Charles Stepney?" asked a friend.

"Hmm, maybe? Sounds familiar."

He spat out a list that went on and on; my mouth opened slightly while I held my phone to my ear and imagined a cartoonish dot-matrix printer firing it all up into the air: records that he knew I had on my shelf. Others that he guessed I had on my shelf. Records I knew by heart, and more than a few that rarely left the unfiled stack near the turntable - the ones you wanna try out in all the moods and reassess against all the weather.

"He's a producer?" asked.

"Yeah, and arranger. You know that Ramsey Lewis album with the White Album covers?"

Oh shit. Yes, I knew that record and I knew what he was getting at. I check in with The Beatles a couple times a year and still love them unapologetically no matter how much free jazz I get into. I'm honestly surprised, but pleasantly. However, when you cut your teeth on those lovable moptops the way I did, you get pretty weird about cover versions. I'm not totally sure why, and I know it's no way to act. Wilson Pickett's "Hey Jude" could put any argument to bed all on its own, and hell, The Fabs did covers too. A tune can be transformed just like anything else. And maybe that's what I require, if for no other reason than that the source material is so ingrained in my memory that my judgment is based entirely on how much I dig the deviation - the reimagination. In some ways, this is a perfect measure of creativity, melting down sacred cows and fashioning new ones.

And so by that measure, Ramsey Lewis' 1968 album Mother Nature's Son - the record my friend was talking about - is one of the most creative records I've encountered. It's also fun as hell to listen to. It's outrageous. Over-the-top. A wide, heavy, satisfying blend of a tighter-than-tight Chicago trio with deep, wild, sweeping strings played by a full orchestra. Throw in some early Moog exploration; deconstruct and reconstruct some of the latest melodies from pop chart faves Macca and Long John (remember, the White Album was brand new); add in that we're-a-winner snare to keep everyone honest; mix to drastic dynamic effect. It's more than just a level above other, more cash-conscious stabs at Beatle re-hash, and it's a far cry from The Gentlemen of Swing days. The Argo days.

Rubie and Charles. Photo courtesy of the Stepney Family.

Stepney holding daughter Charlene. Photo courtesy of Rubie Stepney.

More than a little had changed in the world between 1956 and 1968, but perhaps the biggest change in Ramsey Lewis' music happened when Charles Stepney came into the fold, not that the average listener (such as myself) would have known that specifically. Some reinventions, though, are evident without an obvious mile marker, and we don't need a Ken Burns documentary to tell us something we can learn by simply using our ears. The music changed. Stepney, as he did for countless others, helped to guide Lewis into a fully formed sound while providing some truly wild arrangements. Arrangements nobody else was replicating to quite the same effect.

Drop the needle on Ramsey's 1971 LP Back To The Roots and note the fire level jump considerably on the two tracks Stepney is on. They're not dissimilar to the other cuts on the record but there's a little something extra there. It's hard to pin down and it sounds like a late-nite astrology hotline ad when it's described, but some people have a mix of focus, creativity, and personal charm that makes a session special and sets the results apart. Everything loosens up and gets just right -the third bear's porridge. Charles Stepney, it seems, was one of those people.

So how was I not familiar with Charles Stepney? I went on a deep dive after his name reached me. I immediately took a quick mid-day trip to a couple of record shops and found about a dozen Stepney-produced LPs without even trying. But my surprise was compounded by the fact that much of the deep dive consisted of records I already owned. A cursory scan through my shelves yielded the deepest results: those perfect Terry Callier albums; The Rotary Connection; Minnie Ripperton's debut Come To My Garden; that wild ass Howlin' Wolf album. All drastically different in vibe and intention but all somehow connected to a similar musical language.

Stepney. There he is. I suddenly understood. These aren’t Big Ego records. These aren't recordings with a hierarchy or arrangements made to steal the show -big and boisterous as they sometimes are-and by all accounts Stepney was not a Big Ego guy. Could this music even be made by a Big Ego guy? It's unlikely-and there it is again.

Since the dawn of the American recording industry we’ve been encouraged to visualize The Producer. The Supreme One In Charge: in exchange for their gifts we've been conditioned to allow them a wide berth and to judge them with a grain of salt, never fully weighing them against our supposed concept of a decent human being. Mythical LA Cowboys: unapologetically eccentric, summoning genius from the clouds. A star in their own right. Almost certainly a white man.

Preemptively forgiven with no expiration date: Phil Fucking Spector and the Reverberating American Death Dream. A man's man for fashionable men who can't confront their anger. America wants a James Dean who doesn't cry-legend and lore in real time-and anyone who can't deliver the tabloidian goods when America hits the pellet bar gets their name-recognition cord cut early.

So how does a generous family man from Chicago fit into the ongoing American obsession with celebrity, ego and control? Well, I suppose that's up to us. We have, for years, accepted the fruits of Charles Stepney's brilliance without acknowledging the man. I'm certainly guilty of it. It's a very American thing. I never bothered to learn the name of the workaday father of three who put his whole self into his art and who offered it up for me to have forever.

But I know his name now.

by David Brown

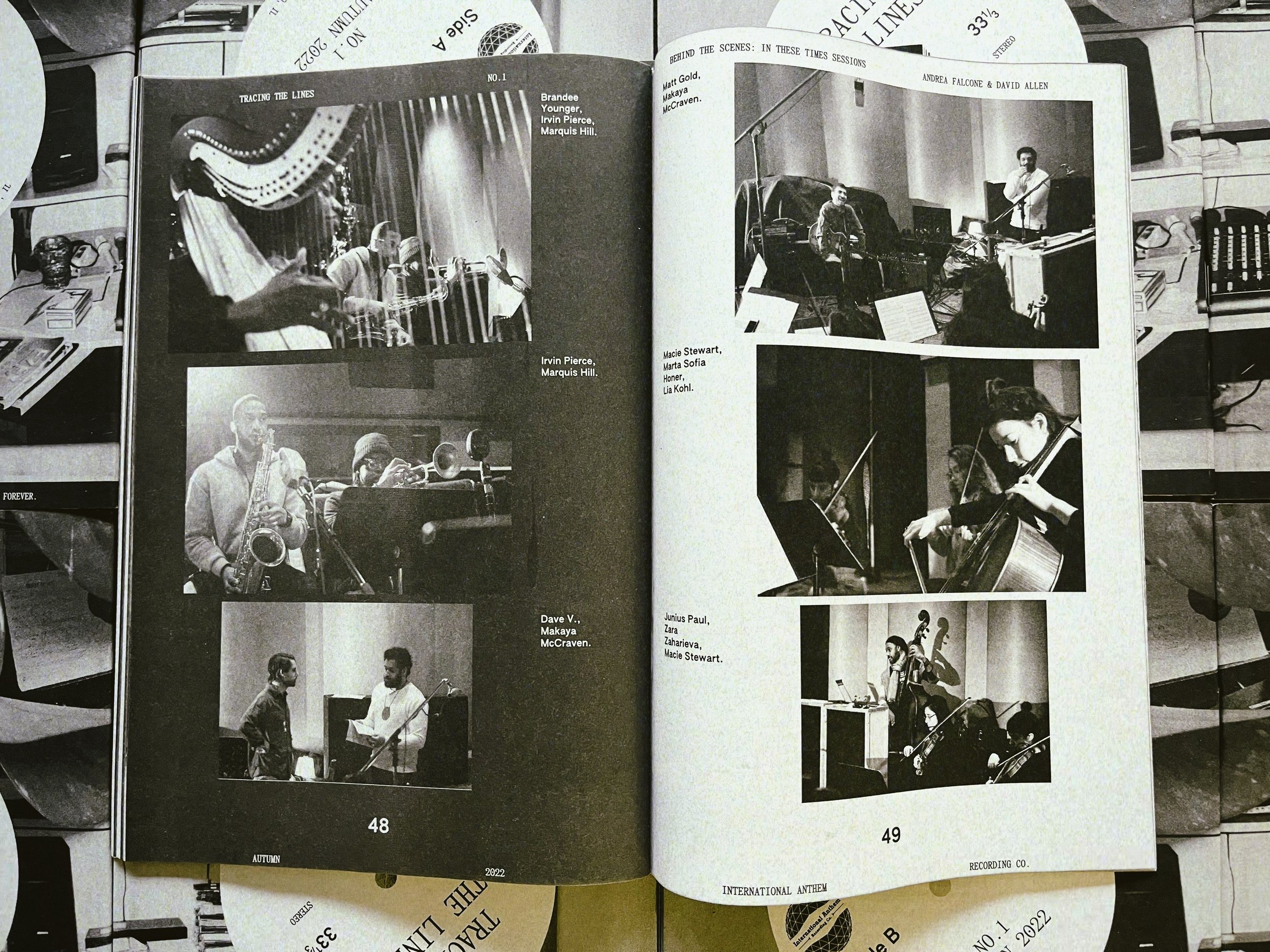

Tracing The Lines is a creative exploration of International Anthem Recording Co. and the community that surrounds it.

Issue #1

64-page 170x250mm newsprint zine, printed in CMYK on 55gsm stock, edited by David Brown and designed by Jeremiah Chiu, with contributions from Alejandro Ayala, André Baumecker, Andrea Falcone, Ayana Contreras, Azul Niño, Carlos Niño, Chris Kissel, Chuck Soo-Hoo, Damon Locks, Dave Vettraino, David Allen, David Brown, Drew Mitchell, Jeremiah Chiu, Kristie Kahns, Lindsey Stepney, Lori Mendoza, Marta Sofia Honer, Scott McNiece, Sulyiman, and Tom Skinner. Made in UK.